From the doors we walk through every morning to the cars we drive and the storage lockers we depend on, lock cylinders are everywhere. Though often overlooked, the lock cylinder — sometimes called the lock core — is the mechanical heart of any locking system. It’s the part that decides who gets in and who stays out.

Whether in homes, commercial buildings, or vehicles, the cylinder determines how securely a lock functions. As criminals become more sophisticated and technology continues to advance, understanding how lock cylinders work — and how to choose the right one — has become essential to ensuring safety and preventing unauthorized access.

This article dives deep into what lock cylinders are, how they operate, what components they contain, and the modern security features that distinguish a basic cylinder from a high-security one. It also explores common attack techniques, maintenance practices, and future trends shaping the evolution of mechanical and electronic cylinders.

A lock cylinder is the central mechanism inside a lock that interacts with a key to control the locking and unlocking process. When you insert a key into the cylinder, you’re engaging the internal components that determine whether the plug can rotate and move the bolt or latch.

The lock cylinder sits within the larger lock body. Its role is straightforward yet crucial — it verifies the authenticity of the key. If the correct key is used, the cylinder allows rotation; if not, it resists any forced manipulation.

Cylinders are used in a vast range of locking systems — from simple padlocks and door knobs to complex master-keyed systems in office buildings or high-security facilities. Their construction can vary depending on the level of protection required, but most rely on precise mechanical interaction between internal parts like pins, springs, and shear lines.

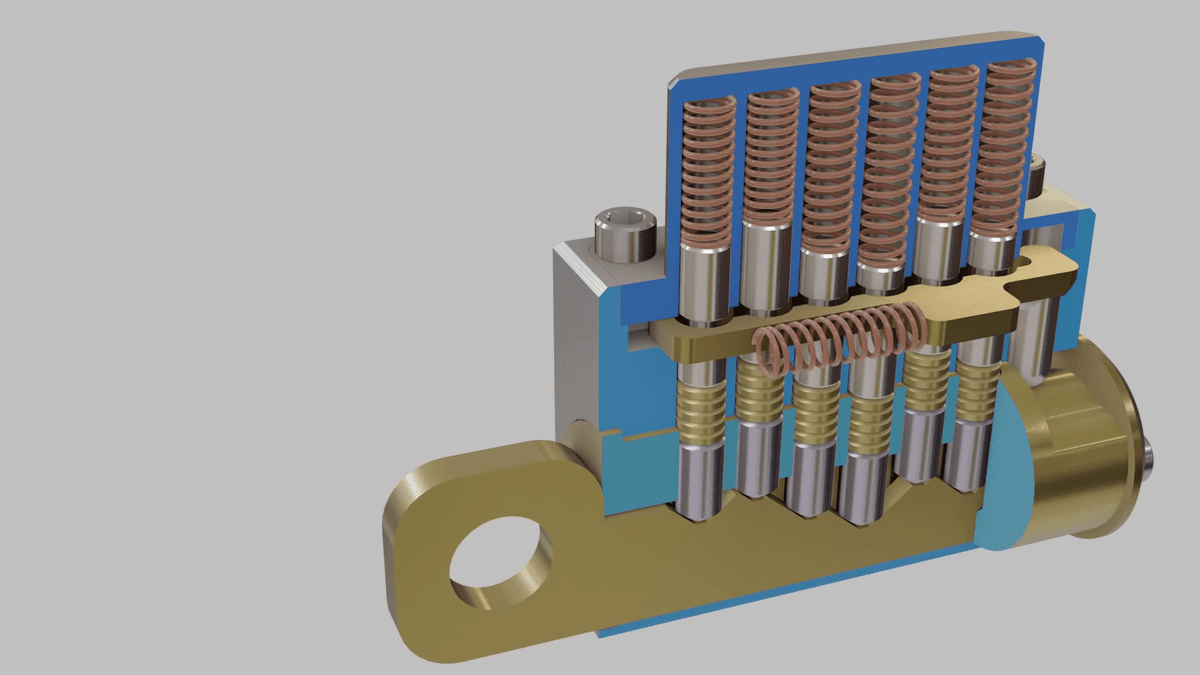

At the core of every lock cylinder lies a delicate balance of components designed to prevent unauthorized rotation. The two main parts are the outer housing (or shell) and the inner plug (or core), which holds the keyway.

Between these two elements exists a critical interface called the shear line. This is where the magic happens. Unless the pins inside the cylinder align exactly at this line, the plug cannot rotate, and the lock remains secured.

Step-by-Step Function:

Insertion of the Key: The user inserts a key into the keyway, which runs through the center of the plug.

Alignment of Pins: Inside the cylinder are several chambers, each containing a pair of pins — a driver pin and a key pin — along with a spring. The unique cuts on the key lift the key pins to specific heights.

Formation of the Shear Line: When the correct key is inserted, the boundary between the key pins and driver pins lines up exactly with the shear line between the plug and housing.

Rotation and Unlocking: With the pins correctly aligned, the plug can now rotate freely, operating the cam or tailpiece to retract the bolt or latch, thus unlocking the door.

Resetting: When the key is removed, the springs push the pins back to their original positions, blocking the shear line once again.

This system, known as the pin tumbler mechanism, remains one of the most reliable and widely used designs in modern mechanical locks.

Understanding the individual components of a lock cylinder provides insight into how different designs enhance security and reliability:

The keyway is the slot where the key is inserted. It’s precisely shaped to match a specific key profile. The complexity and exclusivity of this profile help prevent unauthorized keys from being inserted or duplicated easily.

Most pin-tumbler cylinders contain multiple sets of driver pins and key pins, typically arranged in stacks of five or six. These pins vary in length and are what respond to the key cuts. When the key is inserted, the unique pattern aligns all pins perfectly along the shear line, enabling rotation.

Small coil springs rest above the driver pins. Their role is to push the pins downward when the key is removed, resetting the cylinder for the next operation. The quality and tension of these springs affect how smoothly the key turns and how resistant the lock is to certain attacks, like bumping.

The shear line is the precise interface between the rotating plug and the fixed cylinder housing. The key pins and driver pins must align perfectly along this line for the plug to rotate. If even one pin is misaligned, the plug remains locked.

The housing (also called the shell or body) is the stationary outer portion that holds all internal components securely. It is usually made from brass, steel, or other hardened metals to resist force and drilling.

Located at the back of the cylinder, the cam (in mortise locks) or tailpiece (in rim locks) connects the plug’s rotation to the bolt or latch mechanism. When you turn the key, this part physically retracts or extends the bolt.

Different environments and applications require different types of cylinders. Below are the most common designs used across industries:

Euro Profile Cylinders – Common in European door systems, they are versatile, compact, and come in single, double, or thumb-turn versions.

Rim Cylinders – Mounted on the surface of doors and used with rim locks; popular in older and residential doors.

Mortise Cylinders – Fitted into a mortise lock case, commonly used in commercial and institutional buildings.

Tubular Cylinders – Found in vending machines, mailboxes, and cabinets; easy to use but typically lower in security.

High-Security Cylinders – Include multiple layers of protection such as sidebars, rotating discs, or electronic verification, used in critical infrastructure and high-risk facilities.

Selecting the proper lock cylinder goes far beyond aesthetics or price. The following key factors determine how secure and durable your locking system will be:

Look for cylinders tested under recognized standards such as EN 1303, ANSI/BHMA, or UL 437. These certifications indicate a cylinder’s resistance to drilling, picking, and forced entry.

Brass is common for standard locks, but hardened steel or alloy cylinders offer greater resistance against physical attacks and corrosion, making them suitable for outdoor or industrial use.

Ensure that the cylinder fits your existing door hardware, thickness, and backset dimensions. Misalignment can compromise both usability and security.

In environments where unauthorized key duplication is a risk, choose a system with restricted or patented keyways. Only authorized locksmiths or the manufacturer can cut new keys.

Features such as thumbturns, master keying, or emergency access functions can add convenience without sacrificing security when properly implemented.

Criminals often exploit weaknesses in traditional lock designs. Modern lock cylinders incorporate advanced security measures to counter these threats:

Drilling is one of the fastest ways to destroy a lock’s pins and shear line. Anti-drill cylinders include hardened steel pins, plates, or inserts at strategic points, forcing drill bits to slip or wear out before reaching the mechanism.

Lock picking involves manipulating the pins manually using tools. Cylinders with spool pins, mushroom pins, or false gates create misleading feedback for pickers, making the process extremely time-consuming and difficult.

Bumping uses a specially cut “bump key” and a strike to force all pins to jump momentarily, allowing rotation. Anti-bump cylinders counter this by using staggered pins, special springs, or additional locking bars to neutralize the technique.

In euro-profile locks, burglars may try to snap the cylinder at the fixing screw point to expose the cam. Anti-snap cylinders include a sacrificial section that breaks away harmlessly, leaving the mechanism intact and inaccessible.

With 3D printing, unauthorized key duplication has become a modern threat. Cylinders now use complex key profiles, multi-level keyways, and patented registration systems to make digital replication nearly impossible.

High-security locks often come with registered key programs. Only authorized personnel, verified through documentation or code cards, can request duplicate keys. This ensures tight access control even after years of use.

Lock cylinders are small, but their impact is huge. According to security industry reports, up to 70% of forced home entries exploit weaknesses in door hardware — especially inexpensive or outdated cylinders.

A robust, certified cylinder can delay or completely deter a break-in attempt. Criminals often abandon targets that take longer than a few minutes to breach. This delay, combined with visible deterrents such as reinforced doors and cameras, dramatically improves overall security.

For commercial and industrial settings, the stakes are even higher. A compromised lock can expose sensitive information, valuable goods, or critical infrastructure. High-security cylinders with audit-trail electronic systems are increasingly used in banks, data centers, and government buildings for this reason.

Even the best cylinder will fail if installed incorrectly. Here are some expert tips:

Proper Alignment: The cylinder must sit flush with the door surface; any protrusion can make it easier to grip and snap.

Use Reinforcement Hardware: Fit anti-snap escutcheons, hardened strike plates, and long screws to prevent forced entry.

Avoid Over-Tightening: Overtightening the fixing screw can warp the plug or damage the shear line, causing malfunction.

Lubrication: Use graphite or dry lubricants; avoid oil-based sprays that attract dust and gum up the pins.

Routine Inspection: Check for wear, loose fittings, or corrosion every few months. Replace cylinders showing visible damage or degradation.

Regular maintenance ensures smooth operation and prevents small issues from turning into major failures.

While high-security cylinders offer superior protection, they often come with higher costs and stricter key control policies. In contrast, low-cost cylinders might suffice for interior applications where security is less critical.

The goal is to match the lock to the risk:

Residential Use: A mid-range, anti-pick, and anti-bump euro cylinder with a restricted keyway is generally sufficient.

Commercial Buildings: Mortise or modular cylinders with high-security certification and master key options are ideal.

Industrial/High-Risk Areas: Use cylinders that combine mechanical reinforcement with electronic access control or audit features.

Remember, the lock cylinder is just one part of a larger security ecosystem — door material, hinges, strike plates, and installation quality all play critical roles.

The lock industry is evolving rapidly. Traditional mechanical cylinders are being integrated with electronic, digital, and smart technologies. Hybrid systems now feature RFID cards, biometric sensors, and mobile app control, allowing users to unlock doors remotely while maintaining mechanical backup.

Yet, this progress introduces new challenges — particularly in cybersecurity. Smart locks can be hacked if not properly secured, meaning the shift to digital access must also involve rigorous encryption and authentication systems.

Meanwhile, mechanical innovation continues. Manufacturers are developing multi-point locking cylinders, magnetically controlled pins, and modular systems that allow easy re-keying without replacing hardware. Environmental durability is another frontier, with corrosion-resistant materials and weatherproof designs ensuring longevity even in harsh conditions.

A lock cylinder may be small, but it carries the weight of your security. It determines whether a door is simply closed — or truly locked. Understanding how cylinders work, recognizing their vulnerabilities, and choosing the right features for your environment are the foundations of physical security.

When selecting a cylinder, don’t focus solely on cost — think about the value of what it protects. Opt for models with certified security ratings, reinforced anti-tamper features, and reliable key control systems. Combine them with quality doors, proper installation, and routine maintenance, and you’ll create a barrier that’s both practical and resilient.

In the end, good security is not about eliminating risk entirely — it’s about managing it intelligently. The humble lock cylinder, though often ignored, remains one of the most effective and enduring tools in that mission.